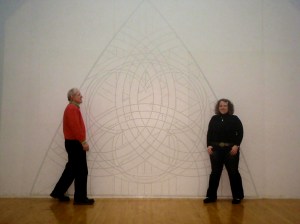

Prof. Rudy Medlock and Paige Medlock Johnson working on the full-size template for the FAS stained glass window.

My father and I have worked collaboratively on stained glass windows for several years. Although he is primarily a stone sculptor and potter, he learned the art of stained glass about 40 years ago and began teaching it in the art department of Asbury University. As a child, I would get off the school bus at the art department and learn alongside the students how to do fiber arts, ceramics, and stained glass, and as an undergraduate student I chose art education as a major with stained glass as my area of concentration. Since then I have worked with him on several commissioned stained glass projects from the Dominican Republic to Kentucky to Scotland for religious and secular institutions, although that demarcation often becomes blurred in the space of installed stained glass.

Stained glass is traditionally an art inherent with ecclesial associations, but now it is found in all corners of public domain; in a sense stained glass is missional as it has migrated from cathedrals to hospitals, homes and pubs, to galleries and libraries and offices. Stained glass is commissioned for symbolic messages, political agenda, architectural decor, for someone’s honor or memorial, and even still for religious purposes and places of worship, such as chapels and temples and churches. What we have traditionally considered distinctly ‘religious’ or ‘secular’ spaces has, in the placement of stained glass, fused or confused those boundaries.

A commissioning body requests a work of art from an artist or studio whom they know to be reputable, and their conceptual design will be for a specific place and purpose, and include a particular image to communicate that purpose. The artist needs to understand the context for the commission in order to create a visual hermeneutic that fills the intended physical space and fulfills the aesthetic and theoretic need. Here is one example of a commissioned stained glass project that changed imagery, artists, and message, illustrating the significance of commissioning theological imagery today.

The Francis Asbury Society is an organization that exists to promote a message of holiness – that people’s hearts and lives can be renewed to live a holy life in connection with God. The message is promoted via publication, itinerant speakers, and retreats and their headquarters recently moved from a modest cramped office space in the basement of an apartment building to an impressive timber frame building at the entrance to the town that is mostly known for Asbury Theological Seminary and Asbury University. Although FAS shares the same name and town in Kentucky as those two institutions, they are not affiliated.

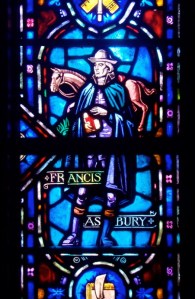

Stained glass window of Francis Asbury installed at The Upper Room, Nashville, Tennessee.

Bishop Francis Asbury was one of men sent by John Wesley to spread Methodism in America, which he did on horseback from 1771 for 45 years. His message, the heart of Methodism, was to spread the gospel and serve people – heart and hand, faith and good works. When the Francis Asbury Society began construction on their new headquarters, a few years ago they envisioned a stained glass window in the center loft space of the building.

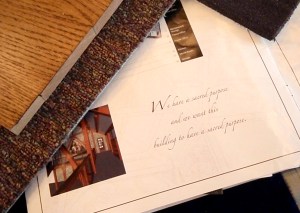

Campaign booklet showing original stained glass image with materials for interior design choices, taken at the studio while working on the new stained glass design.

The overseeing president contacted my father about fulfilling the stained glass project, but upon hearing their desired image, he recommended a different stained glass studio that would be able to work with their desire for a realistic memorial image. After FAS contacted the other studio, the commissioning body still wanted my father to do the stained glass but now they were interested in changing their desired design to a more stylized symbolic image of a Celtic trinity knot, to be interpreted by the artist. They were familiar with The Power of Images and wanted, rather than to honor a person who spread a message, to commission an image of that mysterious message. This was interesting to my father, who then contacted me in Stirling to determine if we wanted to work collaboratively on the project. We both knew the organization and its founder and president, and we both liked the idea of working on a Celtic trinity knot, for its design potential, cultural heritage, and its theological meaning.

The evolving design included a fairly symmetrical geometric modern triquetra with interlocking trefoil, woven through a ring, all superimposed over and interacting with the background of three three-dimensional crosses mirroring the timberframe beams of the building in which it was to be installed.

The stained glass design is about the Trinity, the triune Christian Godhead constubstantial hypostates and relationship between God the Creator, Christ the Messiah, and the Holy Spirit, which is the central mystery distinct to Christianity. Without unnecessarily delving into Trinitarian theology, a simple explanation of the mystery of the trinity is important to understanding why a Christian ministry institution would desire to have this image prominently displayed. This same-essence-different-persons as monotheistic God is not only unique to Christianity but, simplified, is the essence also of Christianity. The illustration of this abstract theological concept by way of triquetra (Celtic trinity knot) and trefoil (architectural triad) is more easily accepted in visual terms than verbal complexity, and it is put forth with aesthetic beauty that is inviting to the viewer.

Like Dewey suggests, this art is experienced as a normal activity, not set apart or autonomous from human living. In fact, this particular stained glass window is installed in the midst of clerical work, scheduled meetings, publications, people in vocation. Unlike Dewey suggests, this art is also experienced spiritually – not set apart from so-called secular living but rather as part of holistic living including the thoughts and the feelings of a spiritual nature. Art can be a spiritual aesthetic experience, not excluded from everyday experience, but rather an everyday experience because it is a spiritual experience, in other words being and doing are not mutually exclusive; it is pragmatic because it is theoretical. This stained glass window can be experienced as artists’ co-creation of visual expression, as theological mystery being wrestled and glorified, as a purely pleasurable moment in passing by, as a creedal affirmation of faith, or even as an invitation to experience the verbally indescribable. It is not so relative that it is not personal, but it is so personal that it is relative.

For visitors to the Francis Asbury Society headquarters now, the stained glass window cannot be missed; as one enters through the front door into the main lobby, the window is centered overhead on the balcony above the main floor entry. Details throughout the building echo the trinity knot motif with wood inlay in the banister woodwork and the unique table configuration in the main meeting room. This stained glass window is here because it cannot not be here. Without it the building would be lacking in visual structure as well as theological foundation. There is a blurring of the sacred/secular where, in this space, the tedium of work becomes infused with the light of something holy while visual theology becomes part of the mundane rituals of work.

FAS stained glass window installed, shows scale, completion, and detailed woodwork.

All photos © Paige Medlock Johnson.