In 2013 Richard Harries’ “The Image of Christ in Modern Art” was published. In his book he outlines four specific criteria for considering a piece of modern art as being ‘religious’. They are:

- All genuine art has a spiritual dimension, just by being good art.

- It is possible to point to the work of believing Christians regardless of their subject matter because it is still an expression of faith.

- It expresses or evokes certain characteristics associated with the Christian faith such as redemption, forgiveness and loving kindness.

- It is related to in some way, traditional Christian iconography. (Harries, 2)

Harries exploration of modern art having to come to terms with and express a seismic rupture as well as contend with expressing faith in an increasingly secular society is laudable and the book is recommended on that basis (it would make an nice companion piece to Tarnas’ Passion of the Western Mind for undergraduates). However, there are a number of areas where issue has to be taken with the treatment provided within the text. For the purposes of this posting I am going to focus on the four criteria and relate them to the specific context of Northern Ireland.

The first criteria immediately rings alarm bells, what is genuine art? Can art exist that is not genuine but false? A quick read through the introduction and first chapter quickly reveals that what Harries means by good art is high art, there is an added layer of exclusivity to the art under consideration. Why then does high art have a spiritual dimension, and low art, by implication, not? The third criteria could have a blog posting on its own on the basis of why are those qualities associated with Christianity alone, when they exist in other contexts including secular ones? However Harries does make it clear he is only dealing with ‘Christian art’ and the Christian faith so I leave that for another time.

It is with the second and fourth criteria that I want to focus in on. Both assume that personal faith, religion to be a distinct and separate thing capable of motivating an individual by force or will. The fourth criteria further assumes a timeless quality and universalism to iconography and its images and symbols. Neither seem to realise, or acknowledge, as Nietzsche did that art is the highest form of expression of the human spirit (The Birth of Tragedy). As such an expression it carries a clear intent for the artist regardless of how well that translates to the viewer. What the viewer interprets comes from his own perspective. Finally, art and artistic expressions are not encapsulated forms of religious expression. In his posting Per-Erik Nilsson argued that:

religion and secularism are contingently articulated categories bound to power and ideology … these articulations have been used to legitimate Western politics and expansion (colonialism, neo-colonial politics and imperialist ambitions).

In Northern Ireland we have a long tradition, on both sides of the divide, of painting wall murals. These are often imbued with what Harries would consider elements of traditional Christian iconography or imagery. Below are two such, the first from Hopewell Crescent in the strongly loyalists Lower Shankill area of Belfast. It depicts Martin Luther nailing his treaties to the Wittenberg door and has a banner stating in German “Here I stand. I cannot help it. God help me. Amen” (Camera did not capture the Amen which is lower down).

Hopewell Crescent, Lower Shankhill Road, photo © Francis Stewart

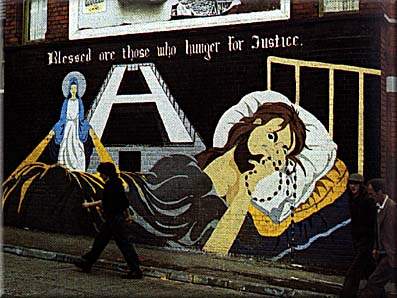

The second is from the nearby Republican area of Divis Street. It depicts the Virgin Mary standing over a dying hunger striker who is saying his rosary and contains the script “Blessed are those who hunger for justice.”

Virgin Mary watches over a hunger striker

Are these forms of Christian art as Harries would perhaps argue (although given they are not high art he may well desist) or are they rather an example of Nilsson’s articulations of categories bound to power and ideology? I would argue for the latter, there are clear political messages in both – the giving of one’s life through starvation for a cause one believes in, and a defence of the very essence of Protestantism, which in this context means a defence of one’s community and right to remain British.

What I would argue about these murals is that they are a means of remembering the past and ensuring that one’s current struggles are not forgotten. Tom Shippey (writing of the works of Tolkien, but none the less pertinent) reminds us:

The very fragility of record in such societies makes memory all the more precious, its expressions both sadder and more triumphant. (Shippey, 97)

The religious imagery, if one can call it that, is used in these murals as a means to an end there is no distinct religious or spiritual impulse behind them. They serve the purpose of telling the past when those in authority or power will not listen. I do not agree that those in weaker positions are voiceless, they are perfectly capable of speaking; those in positions of power must learn to listen. Michael Marten reminds us:

What we need is a realistic exploration of ‘historically specific acts of resistance’ to avoid silencing the subaltern. (Marten, 231)

In creating these murals, the people of Northern Ireland are finding a way round the deaf ears of those in power. They are telling and retelling their history, speaking of their hopes for the future, speaking out against injustices done on them and in the process adding to the further division of the country and the re-entrenchment of their own communities. These are not forms of spiritual or religious art but an engagement with critical religion in that they demonstrate the entire interdependancy of religion, secular, political and power and the tangled web they weave.

——

Richard Harries, The Image of Christ in Modern Art, (Surrey: Ashgate, 2013).

Michael Marten, “On Knowing, Knowing Well and Knowing Differently: Historicising Scottish Missions in 19th and Early 20th Century Palestine” in Ellen Fleischmann, Sonya Grypma, Michael Marten and Inger Marie Okkenhaug, Transnational and Historical Perspectives on Global Health, Welfare and Humanitarianism, (Kristiansand: Portal Books, 2013) p210 – 238.

Tom Shippey, J.R.R.Tolkien Author of the Century, (London: HarperCollins, 2000).