One of the lessons intellectuals should have learnt since the pandemic, I believe, is how quickly both the virus and our knowledge about it and the pandemic could change, diachronically and geographically, to the extent that you may easily feel embarrassed to read some of the viewpoints you published merely two months ago towards a certain part of the world. This applies more to humanities intellectuals than to scientists. While the latter could face with much greater calm their published findings becoming invalid due to the change of context as they are quite aware of the variables (and, of course, their susceptibility to change) involved in their studies and always acknowledge them, the former, on the other hand, has embarrassed themselves much more due to the seemingly more ‘universal’ nature of the statements they made.

Ironically, mutations of the virus and diversity in global governance can also have ‘saving’ effects on an intellectual’s reputation. When Giorgio Agamben sent his messages regarding the pandemic in 2020/21, even those who had supported his critiques of ‘biopolitics’ were eager to draw a line with him, especially when they found that a close parallel could be identified between the way he saw the pandemic and that of right-wing conspiracy theories. In an imaginary caricature, where lifeboats sent by governments are saving people from the COVID-19 flood, Agamben is obsessively shooting at both the lifeboats and the water, claiming that the boats were actually driven by aquatic Nazi zombies under water, as those in the 1977 movie Shock Waves, who will eventually send the boats to concentration camps.

Thanks to both the vaccine and Omicron, the (fatal) flood started to retreat since 2022. While our feet and shins are still in the water, at least people can now walk by themselves, though still stagger from time to time and have to face the risk of falling – especially for those who are relatively dwarf for different reasons. Any “Nazi zombies” left uncovered by the tide? There seems to be, in China, who in the first two years of the pandemic had been seen by many as one of the top students in the global hygienic exam, now considered being obsessed with sticking to their unnecessarily harsh regulations and measures, what Beijing prefers to call ‘dynamic zero-Covid’ policies, even with the price of enormous governmental expense, more deaths (than those associated with COVID) as ‘second disasters’, plunging into a steep economic recession, and increasing impatience from the general public.

Did China see the pandemic as an opportunity for imposing more control over the society and its people from the very beginning and they have therefore consistently implemented their totalitarian biopolitical scheme for nearly three years? Or did Beijing actually follow science when dealing with the crisis of Wuhan in 2020 and only started to send zombies later on when they realised that the pandemic provided a perfect excuse for further domesticating their people and that the new technologies emerged during the pandemic can help facilitate this? In either scenario, it seems that Agamben at the very beginning of the crisis already acutely identified at least the potential danger of ‘techno-medical despotism’.

Did we blame Agamben wrongly? No and yes.

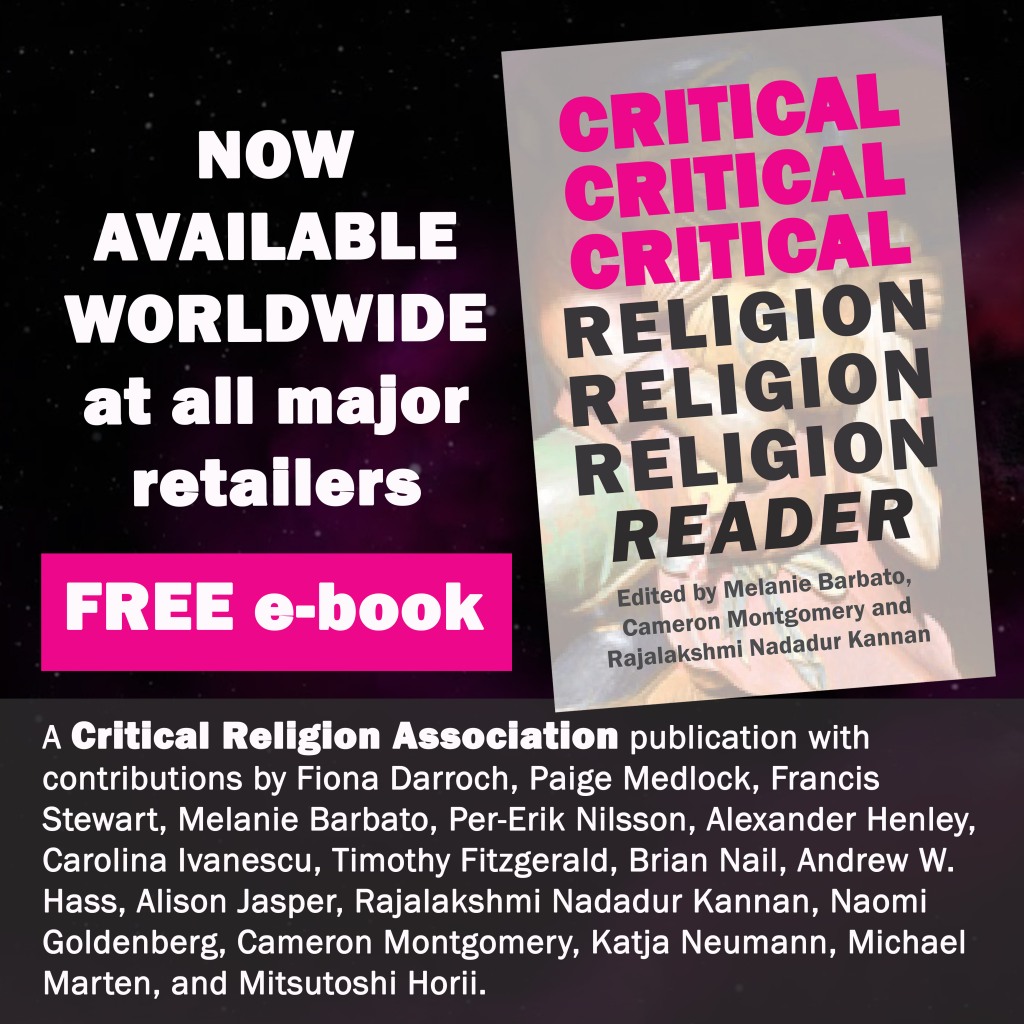

What cannot be denied is that asserting the fictitious nature of a pandemic when we knew little about the disease is nothing but irrationality. It is hard to assume that any western government had had a clear picture about where the virus would bring the world to when Agamben made his earliest comments on the pandemic. Otherwise, they would have moved (much) more swiftly than they actually did. In hindsight, they could not have got a clear biopolitical agenda back then. On the other hand, however, Agamben (2011) has always been consistent, and correct, in denying the binary distinction between modern politics and theology. This accords with, and could be complemented by, the analyses provided by Critical Religion scholars such as Timothy Fitzgerald (2007) about the series of interdependent modern dichotomies such as religion and the secular politics (economics), spirit and matter, body and mind, female and male, superstition and science, etc., and their rhetoric force in shaping the former as private, subjective and nonrational or irrational and the latter as public, neutral and rational, even though these dichotomies are merely constructs and numerous parallels can be found between ‘religion’ and ‘politics’ deemed as two distinct realms of human enterprise.

Studies, such as that of Deborah Brown and Tun-jen Cheng (2015), have drawn parallels (and differences) between the Catholic Church and the party-state in China, which can be illuminating sometimes. However, this kind of comparison cannot make its full sense without recognising the problematic nature of the most fundamental modern binary distinction between religion and the secular. Under the light of this recognition, even those less obvious similarities between modern ‘political’ manoeuvres and ‘religious’ devices can be understood as quintessential parallels.

From the outset of the Christian history, (the Sacrament of) Penance has never been a private affair, as its alias ‘Reconciliation’ indicates. The establishment of Penance was for nothing but reconciliation, firstly with God, and meanwhile with the church, i.e., all in the same mystical body of Christ. That is why in the first several centuries, penance had been conducted in front of the congregation, and its completion pointed to the sinner being taken back by the community. Private penance became more the rule since the 6th century and multiple times of penance were allowed, although public rite of penance only officially ended with the Fourth Lateran Council’s decree in 1215 (McBrien 1994). However, these have not prevented penance/confession from being understood and used by the Catholic Church primarily as a device for adjusting one’s relation to God and the community.

In fact, the whole Catholic sacramental system is described by Paul Tillich (1968, 228) as ‘a system of objective, quantitative, and relative relations between God and man’, managed and actualised by ecclesia. The quantitative and relative nature of this system is a double-edged sword. For Jon Martello, the main character in the 2013 movie Don Jon, a modern-day Don Juan, the weekly penance at church always fix things up. Although watching and masturbating to hardcore pornography distance himself from God, confessions and reciting Lord Prayers and Hail Marys can certainly bring him closer to God again. Nothing to worry about. But for Martin Luther, this quantitative and relative relation apparently meant that he could never do enough in terms of asceticism and merits; the danger of distancing himself from God constantly haunted him, and so did his guilt and the anxiety of losing his salvation. Everything to worry about. What is common to both Martello and Luther, and virtually to every member of the Catholic community, however, is the fact that without certain forms of remedy mechanisms, their existence would have always been in the process of being away from God and excluded by their community. For the community as such, these remedy mechanisms are also ‘immunitary mechanisms’ (Esposito 2011), whose operations protect the community and prevent it from collapse not only from ‘disease’ (sin) but, perhaps even more importantly, from its members not believing the fatality of ‘disease’ (sin) and thus the indispensability of the community for their ‘immunity’ (absolution) and life.

It is such a sacramental system within which millions of people in different Chinese cities are now living. Because of the impossibility of eliminating Omicron, the whole system of immunitary measures can only operate in a quantitative and relative manner. Even though ‘baptised’ with the vaccine, no one can be certain of their ‘salvation’ (immunity), and different manoeuvres have been designed in order to sustain both a certain level of immunity in the society and of people’s belief in the necessity of this inhumane immunitary governmentality. Among these the most prominent for the time being is regular PCR tests. ‘Regular’ means two things: 1) the result of PCR tests determines one’s relation with the community – whether they can enter (most) indoor public places and contact with people in there, including their workplaces; 2) a negative result expires in a certain period of time, usually 48 hours. The result of both is that most people would need to take the test at least every two days if they want to be seen as a ‘legal’ member of the community. One needs to ‘confess’ to the whole community (usually meaning people living in the same city or province) regularly in the form of taking PCR tests – not for committing any definite hygienic foul, but for not being able to prove their personal hygiene since the last test – as the interval between two tests itself implies estrangement from the community and puts the community and its immunity in danger (recall Durkheim!), not to mention that due to the complexity of hygienic casuistry it would be extremely difficult for one not to violate any rule during that time. Therefore, both absolution and reconciliation are needed.

Does this mean one is expected to ‘confess’ as frequently as they can? The uncertainty of ‘salvation’ indeed urges people to do that. One of my friends, with his municipality requiring a 48-hour PCR test result, usually take the test on a daily basis as this gives him more security (of not being excluded by the community). When people travel from a city (or province) to another, this sometimes entails a new test upon arrival, no matter how close the last test before departure was, as the new community requires new ‘confession’ to them. Just as lay Catholics were only expected to follow commandments and monks, on the other hand, should take the full yoke of Christ, that is, counsels, some places require 24-hour negative results from their residents. ‘But I tell you that anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart’ (Matthew 5:28). Within such immunitary governmentality, one needs not get infected to be considered guilty – not ‘confessing’ in time as such would be more than enough to be seen as a behaviour endangering the community, even though there is no cause-effect relation between it and contracting the virus. If you see a crowd who are queuing for a test suddenly parts, like the waters divided by Moses, it is most likely that someone’s negative result was just found having expired two hours ago, and people behave like s/he had caught cholera. For one holding an expired result, although remedy ‘confession’ would be still available, it can only be taken at certain testing stations which are particularly for these ‘sinners’, suggesting a moderate form of segregation as penalty.

All of this, though conducted in the name of science and modern politics, reminds us everything of practices and institutions in history we ‘customarily’ label ‘religious’. It is certainly more than merely about biopolitics as a ‘secular’ sphere of human affair, but neither would it be adequate for us to simply define it as a communist ‘religious’ scheme. Identifying everywhere ‘religious’ as something substantial would only continue the desperate effort in searching for pure ‘secularity’ and perpetuate the false binary distinction between religion and the secular.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. The Kingdom and the Glory: For a Theological Genealogy of Economy and Government. Translated by Lorenzo Chiesa (with Matteo Mandarini). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Brown, D. & Cheng, T. ‘The Vatican and the Chinese Party-State: Where Do the Parallels End?’ Orbis(Philadelphia), 60: 1 (2016), 73–86.

Esposito, Roberto. Immunitas: The Protection and Negation of Life. Translated by Zakiya Hanafi. Cambridge; Malden MA: Polity, 2011.

Fitzgerald, Timothy. Discourse on Civility and Barbarity. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Tillich, Paul. A History of Christian Thought: From Its Judaic and Hellenistic Origins to Existentialism. Edited by Carl E. Braaten. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968.